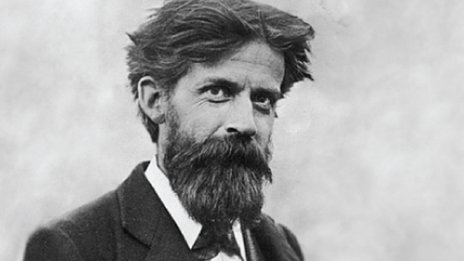

Essay: The Cultural-ecological Imagination of Patrick Geddes (1854 - 1932)

This is the text of the talk given at the second Celtic Summer School at the Scottish Storytelling Centre, inspired by Patrick Geddes (1854 - 1932).

So Who Was Patrick Geddes?

Geddes was Victorian polymath. He was a radical, wildly eclectic and aspirational thinker about places, about communities, cities, cultures, histories, regions, nations, about the world. His life story begins in 1854 Ballater, Aberdeenshire and ends in Montpellier, France, via a childhood in Perthshire, London, Mexico, the Middle east, India and a long stint right here in the heart of Edinburgh’s old town. In the time we have today, I can’t possibly tell you everything you need to know about the man and his legacy. if you haven’t met Geddes before, my hope for this hour is to pique an interest and offer an insight into his cultural-ecological imagination.

Often described as an ecologist, biologist and sociologist, and by some as the ‘father of the Green political movement’, Geddes is probably best remembered for his pioneering work in planning cities. His theoretical ideas have influenced much subsequent planning practice, regional economic development and environmental management. He actually started his career as a geologist before discovering a passion for biology, studying with Thomas Huxley, a contemporary and friend of Charles Darwin. Unfortunately, ill-health prevented him pursuing natural science - suffering from temporary blindness on a trip to Mexico preventing him from looking down microscopes - and so he turned instead to social analysis, applying his scientific methodology to the processes of economic, social and environmental change.

As much as Geddes was a biologist in training, he was a passionate advocate for the importance of the arts to everyday life, developing a cultural awareness to balance his scientific interests. His emphasis on cultural sustainability as the complement to environmental sustainability is absolutely central to his core thinking and imagining, a legacy that is often diluted, or overlooked. That is to say, much has been written on his influence on town planning, but little attention has been paid to the importance and centrality of Geddes' cultural vision. Murdo MacDonald, Professor of Fine Art in Dundee, is one of the few to acknowledge and emphasise this dimension.

Geddes' big project was about bridging the gap between art and science, between environment and society, urban and rural, between culture and nature, thought and action, the academic and the civic. At a very early stage in his career he began on the idiosyncratic path that would take him outside the mainstream of academic life. He had a total lack of reverence for convention and authority and was viewed with suspicion by many of his contemporaries precisely because he flouted academic tradition by deliberately crossing border lines between specialisms. He insisted on the possibility of creating a larger view of nature and of life, a great holistic ‘single discipline’ beyond descriptive special-isms that would bring together art and science, economics and ethics, physics and aesthetics. As a consequence, Geddes was to gain more recognition elsewhere – in India, Palestine, in France – than at home in his native Scotland. The historical ignorance around his work illuminates something of a national condition, afraid to champion its own radical thinking for fear of the charge of narrow-minded provincialism. Geddes’ philosophy was far from provincial, however. His work embodied a particular brand of non-political international and cosmopolitan thinking. The key to his positive and truly global - but not globalising - vision was an anti-xenophobic, outward-looking rootedness in place. His ideas are only now finding their way into wider social consciousness, perhaps because the problems he addressed are more valid and current than ever. Indeed, he is credited with gifting the world the often-used Think Global; Act Local mantra – a phrase all over international policy today.

Kenneth White, in his book On Scottish Ground, notes that it is customary in presenting Geddes to make out a list of his many activities, and classify him as an ‘all-rounder,' but makes the case that this is all too vague. Geddes himself described himself a ‘synthesising generalist’ - I’ll come back to this idea later. Having read many articles on Geddes, I have created my own list for the purposes of today:

“a biologist, a botanist, sociologist, zoologist, scientist, teacher, educator, geographer, geologist, naturalist, urbanist, town planner, ecologist, human ecologist, cultural ecologist, environmentalist, agriculturalist, conservationist, museologist, internationalist, regionalist, generalist, economist, philanthropist, social improver, pioneer, a radical, a peace warrior, intellectual activist, cultural champion, literary man, and a poet! ”

Geddes the Gardener

Among the many titles given to Geddes, the one he himself preferred, allegedly, was ‘gardener.’ The garden became a symbol of the creative interaction of human beings and nature; an ecology in microcosm, so to speak. Here is a picture of Geddes’ bust sitting on a beehive plinth, amongst the bees, in the Storytelling garden, which you are all instructed to go and see when this talk is finished! As a biologist, Geddes studied and wrote widely on bees, and, being the key component in 80% of plant pollination, he, more than most, recognised their vital role on this planet. Today, what are the bees telling us? We are living in a culture out of balance. This ecological metaphor of the story of the bees is a powerful one. Geddes’ priority was about creating the conditions for the flourishing of all life – bee-lieving in a life energy, constantly growing, adapting and seeking expression. He believed that all forms of knowledge - intellectual, cultural, spiritual, creative arts - all reflect each other, driven by this life force.

Geddes was a hive of activity in himself, as were the communities he created, perhaps notably in the old town of Edinburgh. Geddes was a man full of energy, ideas, creativity. His student Lewis Mumford called him the most ‘fully alive person’ that he had ever met. The idea of the beehive, then, evokes Geddes’ life, work and the dissemination of his ideas, which have continued to spread and influence contemporary thinking.

I’d like to read a section from Geddes’ book, The Making of the Future (1916), a chapter called ‘The Revolutionary Type':

“But any forward movement must in the long run proceed on the main lines of our social inheritance, if it is not to fade into sterility or promote reaction. The next inquiry before us must therefore be with the student of the past, accustomed to sweep full circle from that into the present and thence onwards into the future.

What stars do such watchers of the social horizon see brightening in the distance for the comfort and guidance of the disoriented wayfarer? With eyes habituated to the high peaks of history, yet observant of contemporary outlooks and trained to forward vision, what may be discerned of ideals fitted to transform creatures of Law and Custom into creators of Polity, Culture, Art? ”

I want to pick up briefly on this idea of 'wayfaring.' Ecological anthropologist Tim Ingold has recently written about wayfaring in his book Being Alive (2011), in which he argues that our humanity - whatever that might be - doesn’t come fully formed but is continually made and remade in our movements along the ways of life. Life itself, for Ingold, is an ongoing, unending process of wayfaring: ‘My contention,' he writes, 'is that wayfaring is the fundamental mode by which living beings inhabit the earth.'

“Human existence … unfolds not in places but along paths. Proceeding along a path, every inhabitant lays a trail. Where inhabitants meet, trails are intertwined, as the life of each becomes bound up with the other. Every entwining is a knot, and the more that lifelines are entwined, the greater density of the knot. Places, then, are like knots, and the threads from which they are tied are lines of wayfaring”

Wayfarers are their stories, and the stories are unending. Wayfaring always overshoots its destinations, since wherever you may be at any particular moment, you are already on your way somewhere else. Geddes certainly embodies the character of a wandering wayfarer, and and in some ways we could also characterise him as a master storyteller.

What was Geddes' Story?

Geddes belonged to a whole generation of writers and thinkers who were piecing together a critique of the Industrial Revolution and its social consequences. It seemed essential, if there was to be hope for progress in the future, to oppose the continued transmission of established knowledge in the conventional way. What was needed, Geddes suggested, following John Ruskin’s lead, was to create a new way of thinking centred on the production and development of people, not of goods. He wanted to transform the nineteenth century ideal of progress from an individual 'Race for Wealth' into a ‘Social Crusade of Culture,’ underpinned by a vision of mutual co-operation as opposed to competition. Along with the sociologist Victor Branford and rooted in the French ideas of Compte and Le Play, he crusaded for the ‘Third Alternative,’ between unbridled capitalism and socialist state intervention, with the humanitarian object of cultural evolution which would be produced by an interaction of environment, modern knowledge and the historically determined values of the people. Geddes argued that geography, economics and anthropology were so closely related that their union within sociology was sure to yield rich results. Based on his re-imagining of Frederic Le Play, Geddes devised an entirely new system to improve the living conditions of people all over the world, dependent on their specific natural and cultural backgrounds: PLACE WORK FOLK. Place, work and people he writes, 'have not to be separately analysed as into geomorphology, the market economics and anthropology…Within the single chord of social life all three combine.'

Cities in Evolution

Geddes conceived of the city as ‘the organ of human evolution’, playing a creative role as the embodiment of a community’s history, ‘selecting and blending memories of the past with experiences of the present and hopes for the future’. Famously, Geddes proclaimed, 'A city is more than a place in space, it is a drama in time.' His approach to regeneration in his book Cities in Evolution (1915) is based on a holistic and dynamic appreciation of the whole ecological environment. His idea that cities are organic entities constantly evolving in history launched the urban and regional planning movement around the world. In this context, scientific 'facts' - i.e. observations made in a systematic manner - combined with an artistic understanding based on cultural criteria, together made a new subject which Geddes called ‘Civics.’ Taking into account the historic past in order to identify future potential, Civic places emphasis on the interaction between people and place in the context of time.

He set to work in the heart of Old Town Edinburgh, at the time containing some of the worst slums around. Geddes' dreams of a transformed city stood in stark contrast to the contemporary reality, where a massive influx of new arrivals from the country had left the city contending with desperate poverty, high infant mortality rates, and widespread illiteracy. It is important to emphasises that Geddes did not see industrialism as inherently bad, nor did he advocate a return to a rural lifestyle. Rather, he envisioned a post-industrial city, imagining that Edinburgh might one day transform itself 'into a city of happy and healthy artists.'

Today, the Old Town of Scotland’s capital city is a fine example of his architectural practice of ‘conservative surgery,’ the philosophy whereby cities can be kept alive while retaining their original character, saving old structures by re-using them. Indeed, the Royal Mile would look very different today had Geddes not left his mark. Many of the green spaces and gardens you see around the old town are thanks to Geddes.

His many regeneration projects were achieved not through sweeping governmental legislation and measures, but by encouraging involvement by local people in local places through beauty, art and life-long education - giving them agency to change their own world. This approach differs radically from today’s the neo-liberal and statist attitudes to regeneration which often employ a top-down attitude by putting either the state or private property speculators at the heart of developments, regenerating areas but often destroying the communities living there in the process.

Geddesian Lexicon

Geddes created a whole new vocabulary to describe his radical thinking. His neologisms such as 'conurbation', 'megalopolis', and 'habitat', seemed revolutionary during his lifetime, but are now taken for granted. Concepts such as the 'green belt', a means to allow people living in cities to maintain direct contact with nature, are now widely cherished worldwide; and his notion of 'bioregionalsim' - the idea that regions should be delineated by their geographical potential rather than political/economic boundaries - is only now being fully explored as a sustainable development paradigm.

Geddes envisioned human history in stages, and invented names for each:

“Paleotechnics (industrial society) meant waste of natural resources, blighted landscapes, factories, slums. Neotechnics means the use of non-polluting energy and the attempt to reunite utility with beauty, city with landscape. Biotechnics would promote new life thinking, leading to more developed human lives. Geotechnics was the means for human beings to learn how to fully inhabit the earth.”

While his lexicon might seem quaint and perhaps reductive – often full of contradictions - it is a product of his time. It doesn’t take a giant leap of imagination to see what he was getting at. Geddesian sociology and planning took the view that the time was right to progress to a new stage of cultural and economic evolution, or a Green ‘Ethno-Polity’. This was to be achieved via a process of ‘Eu-Polito-Genics’ (the science of good cities). To prevent dismissal of his project as utopian dreaming, Geddes stressed that he was concerned not with creating a utopia, (which translates as no-place) but with the identical sounding Eu-topia, or the Greek for ‘good place’. He advocated not just imagination and utopian projection, but ‘reality-vision.’

Think Global; Act Local

The value concept of ‘place’ was absolutely central to Geddes’ theories of cultural sustainability. For Geddes, ‘place’ starts with the ground on which we stand, and spreads out into our local communities and regions and from there, towards the global. We can add ‘ethnologist’ to the list of his many names! The basis of his thinking is the understanding that a rootedness in a specific locality is the fundamental condition for a truly international and positive global vision. In Geddes’ own words, we must 'Think Global; Act Local.'

Geddes deliberately rejected a narrowly ‘nationalist’ perspective, adopting, for some, what is a commitment to his own interpretation of cosmopolitanism. In Geddes' reality vision, both the 'region' and 'cultural inheritance' are crucial to place, rather than the construct of the 'nation.' A region is defined both by its geology and the work required to make it habitable by human beings, by the relation of country to city, and city to river and sea. From this perspective, attending to local culture is not to be parochial. The very world ‘parochial’ has the same roots as 'ecology,' from para oikos, meaning ‘beside the household.’ From an ecological point of view, rootedness and internationalism are not binary opposites: they are inter-connected – you can dig where you stand but you don't need to get stuck in a hole! His belief was that the more knowledge we have about our own environment, we not only engender a connection and responsibility to that environment, but we see the connection between other cultures and our own.

Synthetic Generalism

I want to return now to Geddes’ notion of 'synthetic generalism.' What did he mean by this?

Murdo MacDonald has written on Geddes and his inherited intellectual tradition of Scottish generalism - a legacy of the Scottish Enlightenment. This is the idea that civic and educational power is generated when, as a matter of course, one area of thought or expertise is illuminated by another and vice versa. Geddes was always looking for connections and patterns and the intellectual tools to bring disparate ideas into relation. Having spent time in India and developing a lifetime friendship with the Bengali polymath and poet Rabindranath Tagore, he was very much open to Eastern philosophy, which he saw as a necessary complement to Western thought.

To explain this rather crudely; our inherited Western paradigm of thought is essentially dualistic, and our analytic, linguistic and positivist philosophies often emphasise the importance of ‘reason’ in contrast to sensory experience and emotion. In this worldview, mind is divorced from body, and the world is divided into the natural and cultural duality of ‘cultural mind’ and ‘physical nature.’ In contrast, Eastern philosophical thinking, based on the embodiment of balance, flow and change, suggests a more complete and holistic view of life than that offered by the mainstream Western traditions.

The key point is that for Geddes, ‘life’ was a single interdependent and 'ecological whole.' We can see this in his wild and wacky ‘thinking machines’ as he called them. The story goes that while he was in Mexico suffering from temporary blindness, he was staying in a room with a square-paned window. Unable to see, he used his sense of touch to think through and work out his ideas on the window's shapes. This is why many of his diagrams are in a grid format, and look like window. The image below, his famous 'Notation of Life' embodies East and Western Philosophy. It is rendered here in 2D but it’s actually supposed to be 3D – and the arrows are the directions of the top layer moving, to indicate that each part of life is connected to the other:

Victor Branford speaks of Geddes as one ‘whose answers to problematical questions are flashed into unity in ecstacies of vision.’ These ecstasies of vision did not translate easily into textbooks, however. Geddes had a profound distrust of what he called the ‘modern habit of verbalistic empaperment’ – that is, publishing your academic research by appropriate means. As a consequence, his officially published works do nothing like justice to his genius. Near the end of his life, in 1931, with reference to Thomas Carlyle, Geddes spoke of the ‘Teufelsdrockian bags of papers’ he felt he had to unravel, much like the hero in Sartor Resartus. He piled up masses of notes and fragments ('idea middens,' as he called them) which rarely got to the state of a coherent opus.

Sympathy, Synthesis, Synergy

Geddes’ ‘visual signature’ was the image of the three doves. These were not just birds evocative of harmony and global peace, they also symbolised three very specific concepts: Sympathy, Synthesis and Synergy. What Geddes meant by ‘sympathy’ was the Enlightenment use of this word, closer to today to what we might call empathy. From this emotional engagement with other people he proceeds to 'synthesis,' the intellectual power of comparing and bringing into relation different ideas, fusing abstract contemplation with the intimate, earthy, sensory and bodily ways in which we experience the world in everyday life, achieved through a balance of ‘heart, hand, head,' his philosophy of education (heart being feelings and emotions; hand - learning by doing; and finally the head being ‘book’ or intellectual learning.) Finally, he moves to the notion of ‘synergy.’ This is thought and action in practice together, a way to solve problems and create opportunities (what today we might call praxis). This holistic, whole body-approach was difficult to stomach for those working in positivist science at that time precisely because it resisted an overemphasis on the rational.

Cultural Imagination

Given the wider context of this Celtic Summer School this week, I want to talk here about Geddes’ cultural imagination. Geddes played a key role in the Celtic Revival, a historical period which witnessed a flowering of artistic, literary and cultural activities. The movement also owed a great deal to the pioneering folklorist Alexander Carmichael (1832 - 1912), who brought to light a vast amount of Gaelic material, here on the left. Oral traditions and the traditional performing arts – poetry, storytelling, song and music – all played a vital part.

The Celtic revival was about re-evaluating the past to learn lessons for a both a Scottish and international future. The shared belief was that, as a nation, Scotland could only be creative when it was actively seeking to implement its own vision of a ‘commonweel,’ with collectivity, rootedness in place and community involvement at its heart. The idea was not to replicate, but to understand, absorb and release the Celtic past into the present, drawing on ancient history, literature, myth and art to produce work in a modern idiom. This revival was 'radical' in the true sense of the word. Radicalis means ‘to form the root.’ The key point here is that this process was not seen as a ‘break’ from history: it was a future reality-vision developed with, not against the past.

In 1885, Geddes formed The Edinburgh Social Union. This was a philanthropic society that was used both as a vehicle to apply his ideas to the social problems of Old Edinburgh and part of an attempt to facilitate the Celtic revival. This work also fed into the wider global Arts and Crafts Movement which was then at its height. Here, artistic ideals were combined with strong political beliefs. Many of those involved in Arts & Crafts – such as William Morris - were reacting to the excesses of Victorian capitalism and industrialism, advocating economic and social reform. Geddes had great support for the ethos of Arts & Crafts because of its pioneering spirit, the appreciation of the joy of craftsmanship, the quality of the materials and the value it placed on beauty as well as life.

Geddes’ own cultural vision is perhaps best embodied in his cultural magazine, The Evergreen. This brought together artists, writers and thinkers of the time to explore the relationship between culture and nature. The name cleverly alludes both to Scottish cultural history and to nature: it evokes Allan Ramsay's collection of poems, 'The Ever Green,' first published in 1714, and to the tree as a metaphor for life. Geddes believed that art holds a supply of folkloric and creative elements that make up the collective memory of a particular society, and part of his mission was to find ways and means to sustain the ecological balance of local and regional arts and culture. The first edition appeared in 1895, containing essays, poems and illustrations structured around the themes of Nature, Life, The World and the North. Each magazine represented a season, with the idea of the seasons as manifestations of the inescapable influence of nature on both the individual and the community. The illustration of Spring is a symbol of hope and renewal. This provided a metaphor for Geddes’ belief in a ‘Scots Renascence’ in which cultural awareness could be restored by a return to local tradition and living nature. This 'renascence' foreshadowed the later literary 'renaissance' which was to flourish in the inter-war period, albeit with a slightly different emphasis. Writers such as Neil Gunn were particularly influenced by the Celtic Revival.

In the final edition of Geddes’ Evergreen, we are told:

“To see the world, to see life truly, one must see these as a whole...Our arts and sciences are but so many specialised and technical ways of showing the many scenes and aspects of this great unity, this mighty drama of cosmic and human evolution.”

The magazine itself is structured to reflect this systematic harmony, with all its contributions constituting the ‘whole.’

The poet Hugh MacDiarmid, in his autobiography The Company I've Kept (1966) reflected, ‘His constant effort was to help people think for themselves and to think round the whole circle, not in scraps and bits. He knew that watertight compartments are useful only to a sinking ship and traversed all the boundaries of separate subjects.’ This said, breadth of thought and a general direction, for Geddes, are not opposed to specialised thought and detailed work: 'they are complementary and mutually indispensible.’

The importance of a sense of 'wonder,' in Geddes’ view is the seed of knowledge. In his final lecture to his Dundee Students, he declared:

“Star wonder, stone and spark-wonder, life-wonder and folk-wonder: these are the stuff of astronomy and physics, of biology and the social sciences…To appreciate sunset and sunrise, moon and stars, and the wonders of the winds, clouds and rain, the beauty of the woods and moon and fields – here are the beginning of the natural sciences. ...

..We need to give everyone the outlook of the artist, who begins with the art of seeing, and then in time we shall follow him into the seeing of art, even the creating of it…

This general and educational point of view must be brought to bear on every specialism. We must cease to think merely in terms of separated departments and faculties and must relate these in the living mind; in the social mind as well - indeed, this above all.”

As Philip Boardman put it, Geddes ‘held constantly before both teachers and students the single goal of reuniting the separate studies of art, of literature, and of science into a related cultural whole, which served as an example to the universities still mainly engaged in breaking knowledge up into particles unconnected with each other or with life.’

Here lies Geddes’ remarkable talent: to see relations and make connections. The motto of the Geddes school was Vivendo Discimus, which translates as 'By Living We Learn; By Creating We Think.' These sayings reflect Geddes’ core ideas that learning should be rooted in real life experience and that the best original thinking is a creative process.

Summer Meeting

One of Geddes' many initiatives was his series of Summer Meetings, where people came together to learn about progressive thinking and new ideas. The teaching method that Geddes helped to pioneer offered adult education classes which bridged art and science. This was revolutionary, and the first of its kind in Europe. These meetings attracted an impressive range of writers, speakers and key thinkers of the time and involved a full programme of talks, lectures, social and cultural events and evening musical concerts as well as opportunities to learn ‘life skills’ and crafts, including architectural work, building construction, woodwork, furniture and art. Participants included geographer Elisee Reclus, political economist James Mavor, Russian anarchist Prince Peter Kropotkin, Scottish singer and composer Marjory Kennedy Fraser, American psychologist and philosopher William James and German biologist Ernst Haekel, who was credited with first coining the term 'ecology.'

The 'Valley Section'

One of Geddes' most famous contributions to knowledge is his regional survey, or 'Valley Section.' This was Geddes’ tool for the 'regional survey,' first published in 1909. The model illustrated the complex interactions among 'biogeography, geomorphology and human systems' and attempted to demonstrate how 'natural occupations' such as hunting, mining, or fishing are supported by physical geographies that in turn determine patterns of human settlement. The point of this model was to make clear the complex and interrelated relationships between humans and their environment, and to encourage regional planning models that would be responsive to these conditions.

Evident in the stained-glass image are Geddes’ categories of folk, work and place: the quarry and the mine in the hill, the sheep and the forest on the hill, arable and cattle farming and crofting on the low ground, and the city with its industry, its trade and its shipping. But on another level this stained glass version of the Valley Section is a multiple representation of what the physical and social world is at the moment and could be in the future. Looking at the Latin wording which appears below this window, we can sees Geddes insisting on a set of at first sight contrasting and yet mutually illuminating views of the valley. The valley is first and foremost an ecology: a ‘microcosm of nature’, but it is also the ‘sedes hominum’, the seat of humanity, the place where human beings make their lives as part of that ecology. And linked to this it is the dramatic ‘theatrum historiae’, the theatre of history, the past experience that should inform the future. Finally, it is the ‘eutopia’ or ‘good place’ of the future, a place that Geddes believed could be achieved through local and international co-operation, and adoption of sustainable technologies.

Geddes’ philosophy for teaching and education were perhaps embodied in his Outlook Tower, now the Camera Obscura at the top of the Royal Mile. This provided both the opportunity to survey the landscape from a height, and to relate this general view to the particular details of geology, botany, zoology, and the sociological, cultural and economic factors which drew town and countryside, individual and community, into a complex pattern of interrelations.

What is Geddes' relevance today?

If we’re thinking of why Geddes’ ideas are important today, we wouldn’t be hard pushed. Geddes’ thinking resonates with many contemporary intellectual and political debates, not least in Scotland, but across the world. The growth of mega-cities, urban decline, obtuse planning and an addiction to suburban sprawl at the expense of vibrant centres, the lack of democratic local governance and the need for integrated policy in all areas are all relevant to Geddes’ thinking.

At this moment in history, the economic and ecological crisis we face demands of us a creative reconciliation of things that have become disconnected and positioned in opposition to each other: between humankind and nature; between the inner world of myth and imagination and the outer world of science, politics, and empirical reality. We must find a new reality-vision.

Geddes had a knack for linking big ideas and expressing them very simply, as in his famous words and truly cosmic story:

“This is a green world, with animals comparatively few and small, and all dependent on the leaves. By leaves we live. Some people have strange ideas that they live by money. They think energy is generated by the circulation of coins. Whereas the world is mainly a vast leaf colony,

growing on and forming a leafy soil, not a mere mineral mass: and we live not by the jingling of our coins, but by the fullness of our harvests.”

This encapsulates the idea that it is the energy coming from the sun, through photosynthesis, that is the creative life force that is the basis of the flourishing of all life.

What might we envision? A future developed with, and not against, past. A model of mutual -cooperation as opposed to competition. Cities that are not dead but very much alive. A society underpinned by a sense of dignity, with greater empathy for others and our own place. A recognition and deep understanding of local cultural inheritance and tradition. A society that involves people in a community of creative artistic expression as a fundamental right, not as something reserved for the privileged few.

There is no doubt that the elements of local 'place' – both tangible and intangible – are absolutely vital in helping people to understand their own and other places in the world. This was the very basis of Geddes’ thinking, understanding that a rootedness in a specific locality is the fundamental condition for a truly international and global vision. Following Geddes, we must work towards developing a respect for a collective sense of cultural values and appropriate actions leading to a sense of ecological responsibility, wherever we find ourselves. We may be able to create ‘sustainable ways of living’ out of bits and pieces selected from diverse cultures across the globe, but it would be wholly unwise to attempt this without first understanding them in their original contexts, and appreciating the consequences of taking them out of those contexts.’ This is the very essence of Geddes. He achieved so much because of his ability to think always from the perspective of the culture of which he was part, utilising the relevance both historically and with respect to the cultural benefits for today’s world.